Tags: Accounting, Content, Flipped Classroom, Student Choice, Video

Description

When a classroom is typically “flipped,” course materials are introduced online before face-to-face class time, and face-to-face class time is focused on application of what the student has learned online. The instructor’s primary role in the face-to-face classroom is to coach and facilitate, rather than lecture. But how best to blend the two learning environments? Integration of the two settings is key; in a summary of the literature, Talbert (2018) shared that students are more likely to engage in the online materials and activities when they perceive them to be meaningfully related to the face-to-face portion.

In the broadest definition of a “flipped” classroom, the instructor is the one designing and facilitating the online activities before the face-to-face time. Less focus has been paid on the role of the students in the production of online materials and activities. When students create learning resources for each other, it encourages a more active learning stance in the classroom (Reyes-Foster & deNoyelles, 2018; Velez, Cano, Whittington, & Wolf, 2011).

While it appears there are learning benefits to having students create materials and teach each other, it is important to offer deliberate guidelines and support to encourage students to produce quality content within a flipped environment.

Link to example artifact(s)

Instructor: Mike Kane, Rochester Institute of Technology

Since September 2014, I produced numerous online lectures for accounting and financial spreadsheet courses in my flipped classroom. Five semesters later – during the spring semester in 2017 – it was time for a change. Instead of me, my students generated their own flipped classroom lectures for their financial spreadsheet courses. Examples of Microsoft Excel topics explained by my students included: auto-fitting, conditional formatting, headings, cell styles, borders, zooming, and date formats. To this end, over 150 videos – generated by me and my students – were originally posted in a YouTube channel and then downloaded to my university-wide course management system.

To maximize use of those videos and for assessment purposes, I incorporated a one-point assessment quiz for each video in the course management system. For each semester-long course, my students completed 100 online video quizzes both in and outside of the classroom.

Asking students to produce their own flipped lectures required a new set of thinking for both the teacher and students. Below are tips that will help develop guidelines for students producing their videos for the benefit of their classmates.

SYLLABUS: INFORM EARLY

Talk about this student-centered technology project at the start of the academic year. Emphasize the main benefits of this project: students engaging in technology while teaching others. Include this graded curriculum component on your syllabus. Explain that you will provide a detailed description of this project and rubric later during the academic term. This ensures no surprise for the students as the academic term progresses along.

PREVIOUS VIDEOS: BECOMING FAMILIAR WITH FORMAT

Students benefited from watching several videos that were produced by students in past academic terms. Viewing those videos gave the students a feel for what was expected of them during the completion of this project during the semester. I encouraged the students to keep the video lengths short. Shorter videos translated to greater motivation toward completion. Watching several good videos will encourage students to ask the instructor follow-up questions. Another bonus of these videos is that it gives the student a feeling of confidence that this can be done.

TOPICS: STUDENT OWNERSHIP

Develop a list of potential course-related topics for the students to choose from. Students like options and/or the opportunity to self-select a relevant and unlisted topic related to the course. My teaching experience in the classroom is such that average students will pick easy topics. That’s okay. If an above-average student selects a too-easy topic, I encouraged the student to select another topic that was more academically appropriate for him or her.

CONTENT: START WITH A FAVORED INTEREST

To get a jump-start toward creating content on a spreadsheet for a selected topic, encourage the student to think about his or her favorite hobby, sport or interest/activity. A student who aspires to be an event planner listed costs associated with party events in a spreadsheet; the student then demonstrated the use of the minimum function involving those listed costs. Another student enamored with British royalty demonstrated the use of the count function through Excel “counting” the number of English kings since 1800 entered in a spreadsheet. A third student who loves watching National Football League (NFL) games showed his classmates on how to change themes in a spreadsheet showcasing various NFL team logos.

DRY RUNS: PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE

I chat with each student to discuss potential content after topic is selected by the student. I find this aspect – creating content – the most difficult video-related task for most of the students to master. The student is forced to think about teaching and how to create curriculum components to complete a video lesson plan. After the student shares with me about his or her personal interests, I allow the student time to input data (the less, the better) and undergo several dry runs with an imaginary camera on top of his or her laptop or computer screen in the classroom. Even better is a dry run at the studio supervised by me or an online learning department worker. Mistakes with delivery or content will be corrected during this dry run process. Depending on confidence with technology and experience with interacting with a video capture software, some students do this quickly; others not.

RUBRIC: STUDENTS CRAVE FOR FEEDBACK!

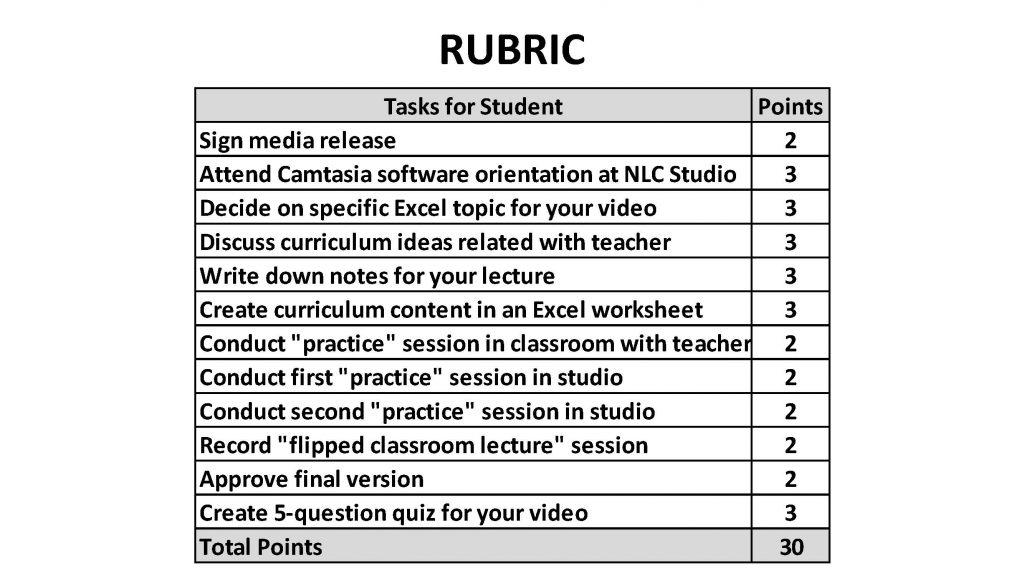

In my case, each completed student-generated video was worth 30 points. Those thirty points constituted only 2% of the entire course grade for the entire semester. It was meant to be a light project, nothing heavy-handed – focusing on critical thinking skills needed for today’s workforce. The rubric is found in Figure 1. Once a video was finalized by a student, reviewed by me and accessibility issues resolved, I receive the final approval from the student.

COMPETITION: TOP STUDENTS WINNING PRIZES

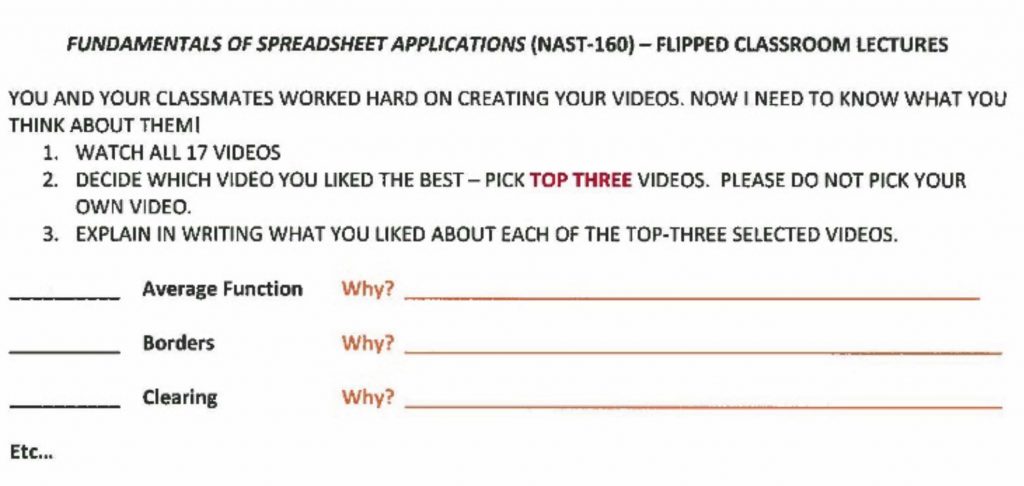

To generate excitement, I created a friendly top-three anonymous vote competition (Figure 2)– prizes are given to the top or the top 3 winners during a final examination period. Each student must vote for others, not for the video that he or she made. The students need to explain the rationale behind his or her votes. Those student responses, also, allow an unique opportunity for the instructor to develop an even more detailed (or informal) rubric of videos, such as appearance, looking in the camera, communication, body language, delivery, appropriateness of content, length of video and real-life applications.

SURVEYS: VALUING STUDENT RESPONSES

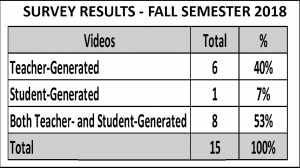

After student videos are completed, posted and shared with classmates, create a different survey each academic term. I asked the students if this experience was a positive learning experience or not. My overall observation is that students enjoy ALL the videos in the classroom which is a respite from learning Excel tasks on a separate educational software website – Cengage. Inquire them if they prefer teacher-generated videos or student-generated videos and the reasons behind their decision. My survey results (Figure 3) revealed that students like videos generated by their peers as well as the teacher. Students selecting teacher-generated only tend to view me as the only “authoritative”/”qualified” person to teach.

Link to scholarly reference(s)

Reyes-Foster, B., & deNoyelles, A. (2018). Using the photovoice method to elicit authentic learning in online discussions. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 7(1), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.14434/jotlt.v7i1.23596

Talbert, R. (2018). What does the research say about flipped learning? Retrieved from http://rtalbert.org/what-does-the-research-say/

Velez, J. J., Cano, J., Whittington, M. S., & Wolf, K. J. (2011). Cultivating change through peer teaching. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(1), 40-49.

Citation

Kane, M. (2020). Flip the classroom with student-generated online lectures. In A. deNoyelles, A. Albrecht, S. Bauer, & S. Wyatt (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning. https://topr.online.ucf.edu/flip-the-classroom-with-student-generated-online-lectures/.Post Revisions:

- August 13, 2020 @ 18:41:11 [Current Revision]

- August 13, 2020 @ 18:41:11