Designing assessments that provide multiple ways for students to demonstrate achievement removes barriers that may exclude students from being academically successful (Tobin & Behling, 2018). For example, writing a paper situates writing skills and language proficiency as precursors to demonstrating learning achievement, even if writing is not a course objective. Digital tools afford flexibility in how students demonstrate learning fostering a more inclusive learning experience. However, leveraging digital tools to increase inclusive access requires thoughtful pedagogical design. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework presents a conceptual model educators can use to design more inclusive assessments, offering students multiple means for demonstrating learning (CAST, 2018; Meyers et al., 2014). Allowing students choice in how they demonstrate learning empowers them to leverage their strengths and preferences, regardless of their circumstances (Tobin & Behling, 2018). The UDL framework operates on three guiding principles each of which activates a neural network essential to learning. These principles and corresponding networks are as follows: (a) Principle 1: Multiple means of engagement activate the affective network or the “why” of learning; (b) Principle 2: Multiple means of representation activate the recognition network or the “what” of learning; and (c) Principle 3: Multiple means of action and expression activate the strategic network or the “how” of learning (Meyers et al., 2014). While an asynchronous online course environment affords student interaction through digital tools, being a successful online student requires strong self-regulation (Barnard-Brak et al., 2010). Highly structured learning experiences support the academic success of nontraditional students (i.e., first-generation, historically underserved groups (HUG), Pell-eligible) (Hogan & Sathy, 2022) who are more likely to struggle in online courses (Xu & Xu, 2019). Pairing UDL with Winkelmes et al. (2016) transparent assignment design (TAD) affords student choice while supporting academic success defining an assessment’s purpose, task, and grading criteria.

Strategy Implementation

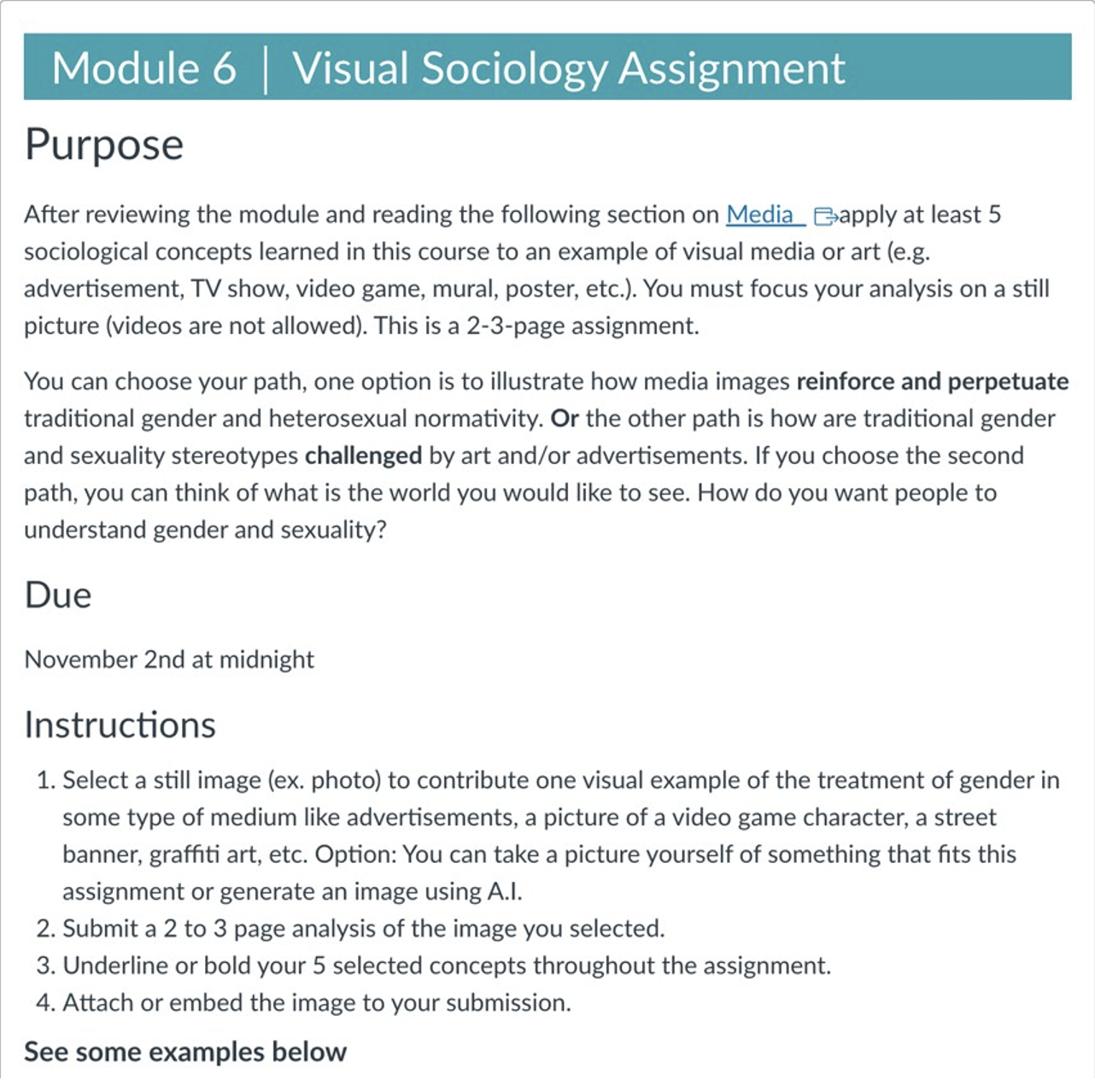

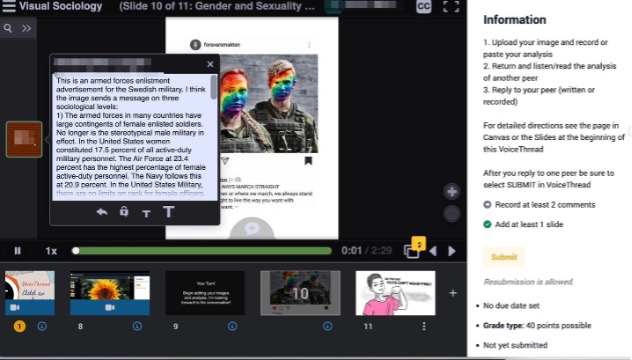

UDL and TAD were used to redesign a written assessment in an asynchronous online undergraduate sociology course on gender and sexuality at a four-year public university designated a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI) with more than 50% of students identifying as HUGs, first-generation, and Pell-eligible. The redesigned assessment incorporated a multimedia tool, VoiceThread providing students the option to demonstrate learning through written, audio, or video commentary, and engage in an interactive peer-to-peer asynchronous discussion. The initial assessment was a three-page Visual Sociology paper. The task was to locate a media artifact that perpetuated traditional gender and heterosexual normativity or challenged traditional stereotypes. The paper was to include an analysis applying five sociological concepts. Specific to UDL, the assessment provided multiple means of engagement. Students could choose their media and sociological concepts for analysis. However, requiring a written assessment positioned writing competency and English fluency, skills unrelated to course outcomes, as prerequisites demonstrating achievement of course outcomes.

Figure 1: Initial Written Assessment formatted using TAD

Figure 2: Course Outcomes.

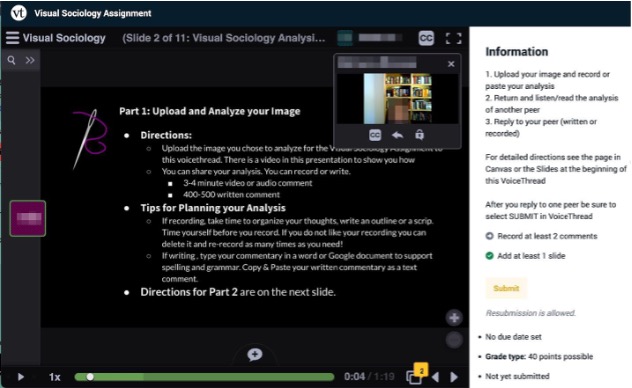

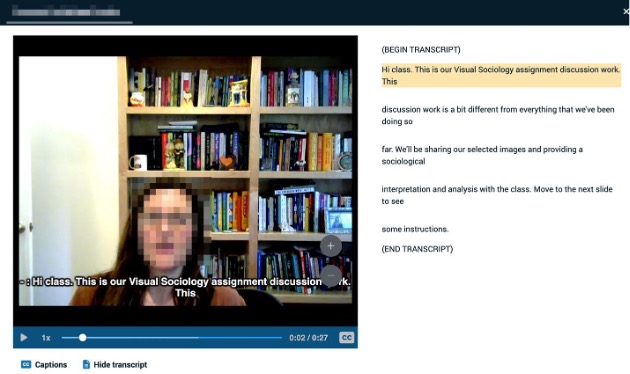

Revising the assessment using VoiceThread retained the same purpose and learning objectives, but provided multiple means of representation, action, and expression. Students could choose a text, audio, or video format to “represent” their learning. The instructor provided written and auditory explanations of the purpose and task directions. With automatic captioning and transcription, students could read or watch recordings from all participants. An asynchronous discussion provided multiple means of action and expression since students could choose how to present their learning while remaining in control of their pacing. Those who chose to submit an audio or video recording could write a script, record, and rerecord, until confident in their presentation. Those choosing to write could leverage word-processing tools. Students had agency in the mode of action (i.e. speaking or writing) and flexible time to express the best version of their knowledge.

Figure 3: Instructor providing multiple means of representing instructions.

Figure 4: Closed captioning and transcript.

Figure 5: Student choosing a written commentary.

Artifact 6: Student image with time to return to add commentary.

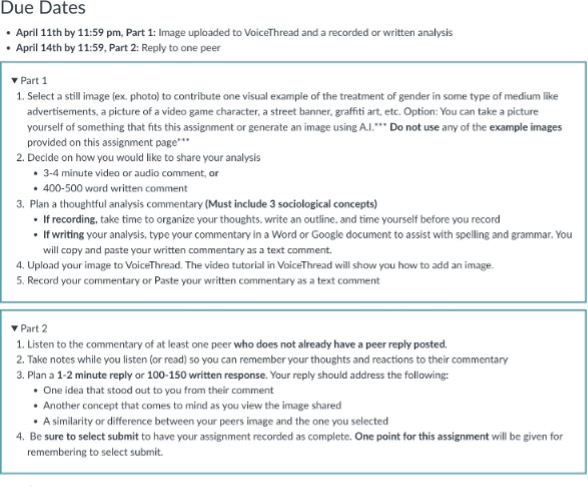

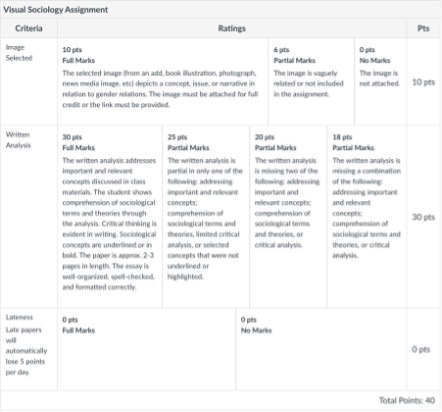

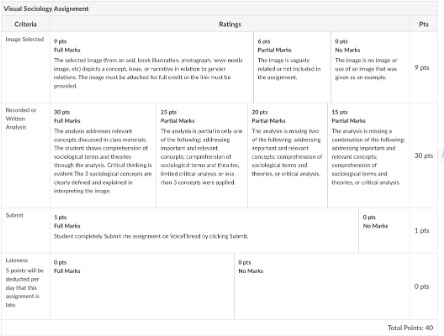

Both assessments used TAD to articulate the purpose, connecting the knowledge and skills students would demonstrate to course outcomes, step-by-step directions for navigating the task, and a rubric defining the grading criteria. To apply UDL the assessment task was divided into two parts to define expectations for posting and replying. Both parts included expectations for recording length or writing word count. Part two included prompts to guide replies. Adjusting the rubric took minimal revision, namely replacing “written analysis” with “analysis”. Applying UDL increases student choice but does not change the learning objectives being assessed.

Figure 7: Revised Assessment Directions using TAD

Figure 8: Initial Assessment Rubric

Figure 9: Revised Assessment Rubric

Figure 10: Peer audio replies with captions

Instructor Reflections

Following the assignment revision, the instructor shared that she personally felt the students benefitted from the opportunity to both create a post for an authentic peer audience and reply to the work shared by others. She found that students’ initial posts and replies, whether written or recorded, reflected the deep thinking and connections to the course content she had intended the assignment would

demonstrate. From a grading perspective, while still time consuming, she found it more interesting and meaningful to review students’ work appreciating the variety of mediums (i.e. written or recorded) as well as the feel of an authentic conversation, seeing their thinking through both their post and their replies. The instructor shared that one of her students had a hearing impairment. Upon review of the student’s submission, they had posted a text-based entry, but peers had left recorded comments; however, the automatic captioning meant the student could engage fully in the assignment without requesting further accommodation. See Figure 10. Combining UDL and TAD increased student-to-student engagement and supported the diverse needs and preferences of students.

Scholarly Reference(s)

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Barnard-Brak, L., Paton, V. O., & Lan, W. Y. (2010) Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(1) pp 61-80. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.769

Hogan, K. A. & Sathy, V. (2022). Inclusive teaching: Strategies for promoting equity in the college classroom. West Virginia University Press.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST.org.

Tobin, T. J. & Behling, K. T. (2018). Reach everyone teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

Winkelmes, M.-A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success. Peer Review, 18(1–2), 31–37.

Xu, D., & Xu, Y. (2019). The Promises and Limits of Online Higher Education: Understanding How Distance Education Affects Access, Cost, and Quality. In American Enterprise Institute. American Enterprise Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED596296

Citation

Eberhardt-Alstot, M. (2024). More Inclusive Assessment: Applying the UDL Framework and Transparent Assignment Design (TAD) to Reimagine a Writing Assignment as a Multimedia Asynchronous Discussion. In deNoyelles, A., Bauer, S., & S. Wyatt (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning.