As an online instructor, do you feel frustrated when students do not read your course announcements, discussions, e-mails, or other written communication? What if we could capture attention by borrowing online marketing copywriting secrets designed to cut through life’s distractions? Online marketers are copywriting masters. Copy is text-based content that persuades readers to act (Dodds, 2020). This article will share Internet copywriting concepts that you can use to transform your messages from unread to attention grabbing.

Understand your Intention

As educators we want to share and explain everything. Today’s online learner, however, doesn’t have time for everything. Before you send an announcement, message, or other communication consider why you are sending written content to your students. Content typically falls into one of three categories (Taylor, 2008):

- Inform: What do you need students to know? Pick one key topic and one call to action.

- Educate: Education content tends to be longer than basic information. How do you want students to think or do something differently after they read your content? Education content writing is beyond the scope of this article.

- Entertain: What emotion do you seek to evoke? Entertainment, used purposefully and occasionally, can facilitate personality and human connection in your course. Entertainment can be a chief communication purpose, or it may supplement information or education content delivery.

For any intention, you also want the message to stick. Sticky, or memorable messages have 4 key components (Brown, 2014).

- Solves a problem for the reader

- Simple

- Relevant

- Easily repeated

Adjusting literacy level

Once you know your communication’s intent, you need to match your writing to the audience’s reading literacy level. The current average post-secondary student in the U.S.A. reads at the 7th-8th grade level (Marchand, 2017). This intermediate level includes the ability to read and summarize unfamiliar information in a moderately dense text, make simple inferences, and accurately recognize the author’s purpose. 5-10% of post-secondary students, however, exhibit only basic level abilities. Basic abilities include reading and understanding familiar prose, or explaining processes from brief pamphlets or guides (Baer et al, 2006).

When comparing internationally, most countries have similar reading literacy levels to the U.S. as assessed by the 4th grade PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy) exam. Some countries, such as Russia, Singapore, China, and northern Europe demonstrate higher abilities. Some countries in the United Arab Emirates, Balkan region, and southwest Europe scored lower. Since its inception in 2016, the e-PIRLS has demonstrated similar literacy levels for digital formats (Sparks, 2017).

Word selection, grammar, and syntax

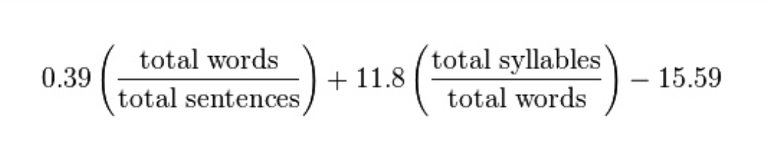

If we want to write at the 7th-8th grade level, the next question is “how?” There is an equation to answer this question. The Flesch Kincaid Grade Level equation calculates grade level for written content (Readable, 2011).

Before you start doing math, start with the basics. The equation is based on:

- Words: How many words do you have? How many syllables are in the words?

- Sentences: How many do you have?

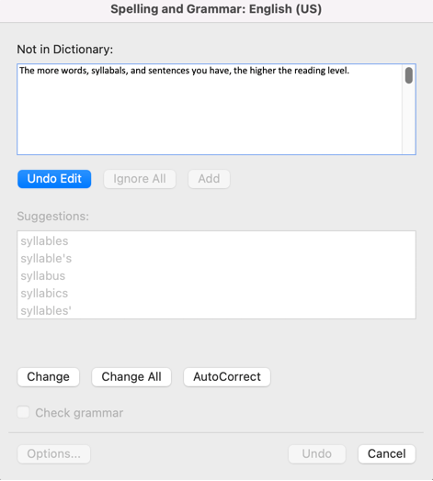

- The more words, syllabals, and sentences you have, the higher the reading level.

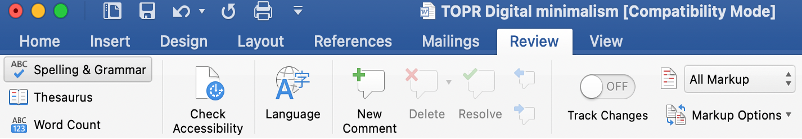

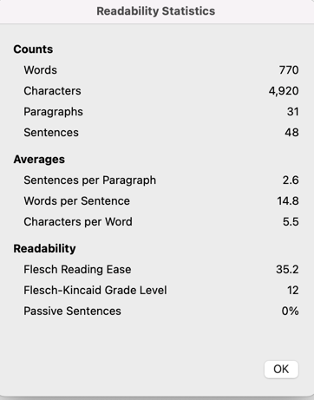

You can use Microsoft Word to reveal your writing’s grade level. After composing your message, follow these steps:

- In Microsoft Word, select “spelling & grammar”

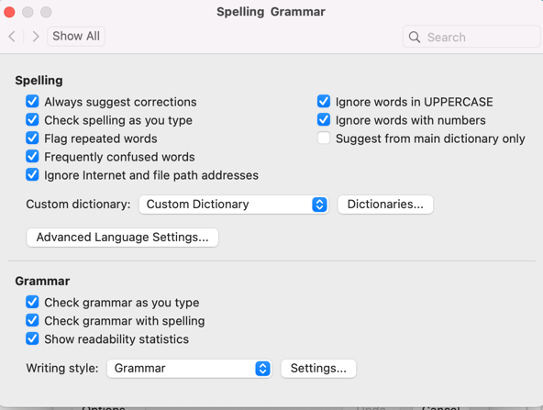

- In the pop-up box, click on “options”

- Check the box for “show readability statistics”

- Close any pop-up windows that are still open. Run your normal spelling/grammar check. At the end, your readability statistics (including grade level) will appear.

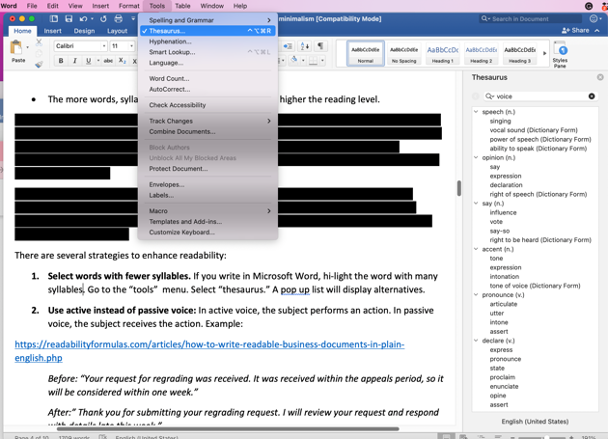

If your readability grade level is too high, revise your writing in 3 steps:

- Select words with fewer syllables. If you write in Microsoft Word, hi-light the word with many syllables. Go to the “tools” menu. Select “thesaurus.” A pop-up list will display alternatives.

2. Use active instead of passive voice: In active voice, the subject performs an action. In passive voice, the subject receives the action (Scott, 2023). Example:

Before: “Your request for regrading was received. It was received within the appeals period, so it will be considered within one week.”

After:” Thank you for submitting your regrading request. I will review your request and respond with details late this week.”

- Eliminate unnecessary or redundant words: Start by eliminating words that fill space while not contributing to the key message (Scott, 2023; Hertzberg, 2019). Examples include (Hertzberg, 2019): “at all times, “each and every,” “in order to,” “basically,” and “that.” Example:

Before: “In order to complete this assignment begin by imagining this: Create a picture in your head that clearly and simply depicts the blood flow through the heart. Now, draw it on paper and submit a photo of your drawing to begin this week’s discussion.”

After: “Visualize the heart’s blood flow. Draw it on paper. Take a photo. Submit your photo as your initial discussion post.”

Humanize your message

The above steps likely led to a shorter message. This improves readability, but should not compromise the human connection. Good writing is like a conversation, not a robot barking orders. Even when the message intent is a quick action like “check your grades,” readers are more likely to engage if the message is humanized. The reader needs to see themselves in the message and feel a personal relevance to their current or aspirational identity (Horberry & Lingwood, 2014). For example, “check your grades,” could be humanized by rephrasing to “see your total course points rise by checking your grades.”

Digital transformation in 6 steps

Now that you know your content’s intent, you have adjusted it for your audience’s grade level, and you have humanized it, you are ready for the digital formatting transformation. Online readers skim text instead of reading word-for-word (Gibbons, 2020). Your formatting directs focus. Focus determines what the reader will take in and potentially use to inform next steps. Follow 6 steps to transform your message for the online reader:

Step 1: Start with an attention-grabbing title.

The title should gives the audience a reason to read (Taylor, 2008). Sprout social offers 6 education environment-relevant ideas for starters (Barnhart, 2020):

- Promise a payoff. i.e. “Save yourself time by _____.”

- Ask a question. i.e. “Why is ______ so important?”

- Get personal by using “We, I, or You” i.e. “How I would study for my own course.”

- Use a number such as a relevant shocking statistic. i.e. “Heart disease is the #1 cause of death. How can we help right now?”

- Keep it short and relevant. i.e. “Submit these 5 items this week.”

- Use power words that imply you are helping students solve a problem. Avoid words that imply someone’s lack of ability or knowledge. Examples:

Use: “Save,” ”Prepare,”” How to,” and “Without”

Avoid: “Can’t,” “Don’t,” and “ Need”

Step 2: Put your communication reason in the first sentence.

The reader is unlikely to spend time searching for your key point (Scott, 2023). Example:

Before: “Nice job completing your module 8 assignments. I really enjoyed how they illustrated so many real-life applications of our key content for this unit. Sending a quick note to let you know that your grades have now been posted.”

After: “Module 8 grading has been completed. Please check your grades. Overall, it was exciting to see how many real-life ways you found to apply the material.”

Step 3: Use Inverted Pyramid formatting.

Inverted pyramid format means putting the most important information first, followed by additional details, followed by non-essential details (Scott, 2023; Patel, n.d.). Readership drops off with each subsequent paragraph, which hi-lights the inverted pyramid format value (Patel, n.d.).

| Paragraph position from start of text | % of readers who look at the paragraph |

| 1 | 81% |

| 2 | 71% |

| 3 | 63% |

| 4 | 32% |

Step 4: Shorten your paragraphs.

8th grade reading level paragraphs typically include 100-200 words in 5-6 sentences (Grammarly, 2020), but online attention-holding paragraphs focus on single ideas and may be as short as 1-2 sentences (Gibbons, 2020). Example:

Before: “Nice job completing your module 8 assignments. I really enjoyed how they illustrated so many real-life applications of our key content for this unit. Sending a quick note to let you know that your grades have now been posted.”

After: “Module 8 grading has been completed. Please check your grades. Overall, it was exciting to see how many real-life ways you found to apply the material.”

Step 5: Use white space to direct attention.

Empty space draws reader attention toward the key points (Patel, n.d.). Instead of putting the key points into paragraphs, put them into bold-face or bullet-point lists. Readers are more likely to pause on this content, as opposed to reading paragraphs. Bold-face type is useful for (Patel, n.d.):

- Section headers

Section headers are like brain-based filing cabinets. They help chunk information into memorable pieces. Section headers can also be used to pique curiosity. Pretend each header is a catchy headline or chapter title that entices the reader to want to read what follows.

- Key terms or concepts

Readers are more likely to scan the bold face terms, then seek additional reading if they have additional questions. Using bold (selectively) helps scanners take in the key points. The same is not true for all caps or underlining. All caps online implies yelling. Underlining online implies a hyperlink.

Step 6: Finish with a clear call to action (Scott, 2023).

A clear call to action specifies a singular action you want the reader to take. The call to action should include how and when to perform the action. Example:

Before: “I hope this summary of what is due this week is helpful. Would you like more summaries like this? Let me know what you think.”

After: “I would like your feedback on whether weekly summary posts are helpful. Please complete this one-question poll before you navigate away from this course announcement.”

Link to Example artifact(s)

In online courses, common places to employ instructor-generated writing include:

- Course welcome

- Course announcements

- Discussion forums

- Assignment feedback

- Live classroom (virtual synchronous or asynchronous lecture/lab) passwords

Let’s view real examples of each:

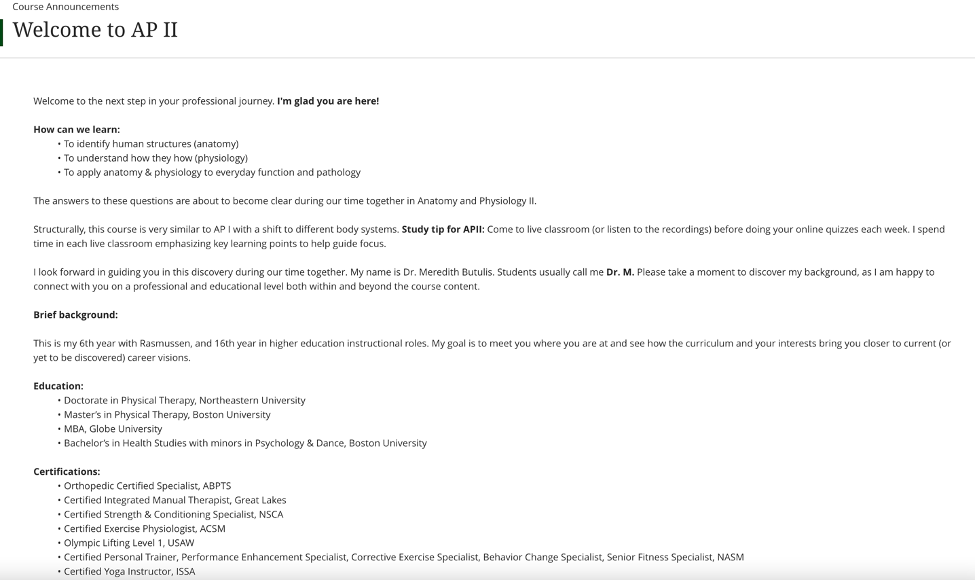

Course welcome

Here is an excerpt from my course welcome. The welcome also includes my picture and a quick on-screen tutorial of how to get started. The welcome employs digital copywriting practices by:

- Using white space, bold face, and bulleted lists to draw specific attention.

- Humanizing by beginning with a welcome, a quick list of what we will learn, and what students should call me by.

- A bulleted list of my credentials to teach the subject with an invitation for students to professionally connect beyond course content. Notably, this list is strategically positioned later in the course welcome, after I’ve shown students that they come first.

The final portion of the course welcome shares 2 truths and a lie. During the first live classroom, I ask students to guess what the lie was. This helps me gauge who read the welcome. It also reinforces the expectations for students to read course announcements.

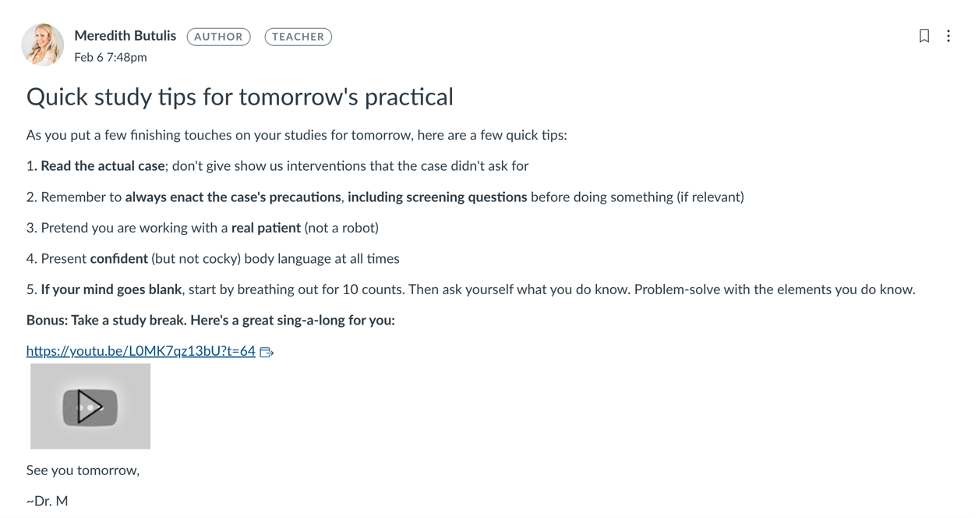

Course announcements

Before exams, student naturally get nervous. Many have difficulty with procrastination and stress management. The following course announcement employs several key digital copywriting best practices:

- A short title that helps students solve an urgent problem

- The use of white space, list formatting, and bold face to help students focus on the key solutions

- Humanization since the tips solve common student problems

- Further humanization with a funny 2-minute Disney sing-a-long link to help students de-stress. Based on learning psychology, I also knew that they would learn more by taking a study break, which this comic video offered.

While this announcement does not include a specific call to action, I knew the students read it based on their actions. Several of them came into the practical exam singing the song that was included in the announcement.

Discussion forums

This discussion example illustrates an instructor post in a graded discussion forum. Students are required to make an initial post and a follow-up post for the week. Achieving full points requires integration of credible resources. Students often need help generating evidence-based content for the follow-up post. The sample post illustrates digital copywriting by:

- A solution to the credible resource-finding difficulty with a direct link to an article on the week’s discussion topic

- The use of white space, and clear call to action

- Humanization by sharing previously published student work with that student’s permission. This helps students see that I value their contributions. Students see how they can become part of the shared learning experience both in the online classroom and in the broad community.

Student engagement can be measured by the number of students that either reply to the post, or use the resource to generate their own follow-up posts for the week.

Assignment feedback

The assignment feedback sample content illustrates that I have read the student’s assignment, and that I recognize the learning sticking point that they mentioned. The feedback offers a flexible call-to-action with both self-help resources and also real-time help resources for the student to follow up. The original version was humanized by beginning with the student’s name. The name was removed to preserve confidentiality.

While I do use video feedback to facilitate human connection in smaller classes, this online class has close to 50 students with 6 assignments per week (due to the course design); scaling video feedback to this level is not feasible.

This particular feedback system does not allow for digital minimalism formatting, but if formatting were an option, I would incorporate white space, bullet points, bold face, and a direct hyper link to the mentioned online resource.

In this example, a student e-mailed asking if I could make a self-study Kahoot! to help prepare for an upcoming exam. Since I could create a Kahoot! quickly to help this student and potentially others, I created one, posted it, and created a course announcement for any student that would like to use the study tool.

I also closed the communication cycle with this student by letting her know where to find it. The e-mail employs digital copywriting with its short sentence structure, and appropriately short nature given the overall context. The brevity of this writing helps the student feel acknowledged and valued without taking away from valuable study, family, and work time.

Live classroom passwords

When we have virtual synchronous sessions, student attendance points are based on their Blackboard assignment link session password submission. Students receive credit by entering the password, and credit is equal based on live attendance or listening to the recording. However, I rarely give passwords. Instead, I ask questions that help me learn how to connect to students and further meet their needs.

The sample illustrates digital copywriting with the short format, use of bold face, and use of white space. It further illustrates humanization through my own picture; this image is relevant to the content since I am asking students to introduce themselves as well.

Here is my module 1 live classroom password slide. I can measure student engagement by the number of students that complete the live classroom password assignment successfully.

Half way through the course, the live classroom password I ask is “what can I do to help you more?” A week later, I ask “what are you enjoying most in this class?” The student feedback speaks for itself:

Next steps: After reading this article, give one of your own written student communications a digital writing makeover. Walk through each step above from beginning to end. As you follow each step, reflect on which copywriting elements you already incorporate, and which novel elements you may want to try. Digital writing makeovers take practice. With practice over time, digital minimalist writing not only improves communication clarity and student engagement, but also saves time.

Link to scholarly reference(s)

Baer JD, Cook AL, Baldi S. (2006). The literacy of America’s College students. American Institutes for Research.

Barnhart, B. 2020. Headline writing: 10 ways to get more eyes on your content. Sprout Social.

Brown, P. (2014). Make it stick: the science of successful learning. Belknap Press. Cambridge, MA.

Dodds, D. (2020). Content writing vs. copywriting in digital marketing: what’s the difference. Forbes.

Gibbons, P. (2020). Copywriting for print vs. digital. LinkedIn Pulse.

Grammarly staff (2020). How long is a paragraph? Grammarly.

Hertzberg, K. (2019). 31 words and phrases you can cut from your writing. Grammarly.

Horberry, R, Lingwood, G. (2014). Read me: 10 lessons for writing great copy. Laurence King Publishing. London.

Marchand, L. (2017). What is readability and why should content editors care about it? Center for Plain Language.

Patel, N. (n.d.). 12 writing and formatting that’ll get your longest posts read.

Readable. (2011). Flesch reading ease and the Flesch Kinciad grade level.

Scott, B. (2023). How to write readable business documents in plain English.

Sparks, S. (2017). Global reading scores are rising, but not for U.S. students. EducationWeek.

Taylor, V. (2008). Complete Guide to Writing Web-Based Advertising Copy to Get the Sale: What You Need to Know Explained Simply. Atlantic Publishing: Ocala, FL.

Citation

Butulis, M. (2023). Capture Student Attention with a Digital Writing Makeover. In deNoyelles, A., Bauer, S. and Wyatt, S. (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning.