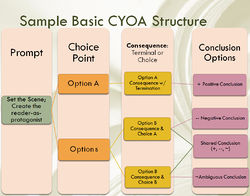

While many instructors across instructional venues integrate collaborative activities that emulate professional realities, collaboration assessments often disenfranchise some contributors. When evaluation hinges on groups producing a cohesive, homogenized artifact, the outcome favors compromise. Homogenized perspectives don’t generally reflect the complementary visions of individuals. This can foreclose on participant satisfaction if the outcome silences or abandons a member’s contributions. Fortunately, a branching, gamebook or Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA)-type strategy affords a solution with both eLearning viability and cross-discipline leverage. Some technology options for the format include presentation software (such as PowerPoint, Keynote, or Google Slides) online programs such as Inklewriter, Google apps, blogs, or other webpage-creation platforms.

In essence students may create their work in the form of branching content, or they may reflect upon their work (and/or the work of others) in a branching style, highlighting key decision points and outcomes. Thus, this approach is suitable for both formative assessments and summative assessments of learning.

The Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) format has 3 guidelines in these assessments:

- Point of View: The story should present a 2nd-person point of view.The main character is scripted as “you” by the learner-author.

As invitation into the story, the reader develops immediate narrative importance.

As a direct address to the reader-protagonist, learner-authors establish a character worldview that can reveal a perspective other than their own. - Present tense:The protagonist’s actions in the story are happening in the moment of reading.Keeping the narrative in-the-now is a rhetorical strategy for urgency.

Present tense puts learner-authors in the linguistic mindspace of “reliving.”

Learner-authors have the chance to serve on double-duty as creators and as reader-protagonists. - Conclude: Every narrative path should reach an end.This final guideline purposely says to conclude instead of resolve. Some content simply shouldn’t have absolute resolution, and in both a formative and summative use, it becomes a platform for further learning.

Link to example artifact(s)

Dr. Stacy Greathouse (Texas Women’s University) recommends starting with a simple branching structure leading to the opportunity to produce more complex narratives as the semester continues. Following are several scenarios in which the CYOA approach is applied.

Example 1

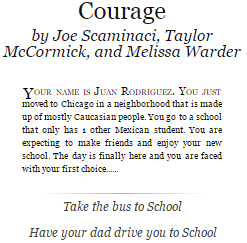

Formative assessment goal: Offer an opportunity for the co-creation of content understanding relative to source material.

Learning Objectives:

- Explore the ideals, beliefs, and values reflected in literature for Middle Grade readers. Model the conventions found in different forms of quality texts and literature aimed at Middle Grade audiences.

- Prompt: Choose a topic of personal or professional interest to you that is also relevant to pre-adolescent literature / culture. Develop a literary and narrative project that would appeal to this Middle Grade audience with depth, dignity and detail. You may base your project on a novel or text from this class as a starting point or construct a completely original narrative.

- Artifact: A story produced by Dr. Greathouse’s students in InkleWriter. (Used with permission.) [Example available: https://writer.inklestudios.com/stories/34mc ]

Example 2

Summative assessment goal: Review content concepts and the learner’s personal responsibility for engaging that content.

Learning objective: Reflect on how new concepts or skills acquired could have helped or hindered learning at earlier points in a unit.

Prompt: Revisit and choose 1 crisis or confusion moment you had working with and/or understanding the content during the Sea Shanty unit. Script at least 2 choices you made at different points in the unit and how they contributed to or solved the confusion.

Additional Options

- Blog option: A single learner-author writes the prompt and provides the first choice based on what the learner actually did. Peer learners offer the choices they made and how it kept them from being confused, or the choices that may have never resolved the confusion, etc.

- Journal option: A single learner-author writes the prompt and provides the first choice based on what was made. The instructor-student interaction takes the form of a dialogue of alternatives, sometimes through questioning, which becomes a dialogue of choice.

- Adaptation Opportunity: Instructor Performance Evaluation As an extension of summative evaluation, instructors can benefit from the CYOA as a retelling of their performance through the semester from the student perspective. Allowing students to script and play the part of the instructor exposes what could have happened if, during those crisis moments, the instructor had chosen differently.

Link to scholarly reference(s)

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (C. Emerson, & M. Holquist, Trans). M. Holquist (Ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Blackledge, A., & Creese, A (Eds.). (2014). Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy: Vol 20. Educational Linguistics. New York: Springer.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clark, M. C., & Rossiter, M. (2008). Narrative learning in adulthood. New directions for adult and continuing education, 2008(119), 61-70.

Egan, K. (2003). Start with what the student knows or with what the student can imagine?. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(6), 443-445.

Hunter McEwan, H., & Egan, K. (Eds.). (1995). Narrative in teaching, learning, and research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Paulus, T., Horvitz, B., & Shi, M. (2006). ‘Isn’t it just like our situation?’ Engagement and learning in an online story-based environment. Educational Technology Research & Development, 54(4), 355-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-006-9604-2

Slabon, W. W., Richards, R., & Dennen, V. (2014). Learning by restorying. Instructional Science, 42(4), 505-521.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1995).Radicalizing childhood: The multivocal mind. In H. McEwan, & K. Egan, Narrative in teaching, learning, and research (pp. 69-90). New York: Teachers College Press.

Citation

Greathouse, S. (2015). Assess individual learning from group projects. In B. Chen & K. Thompson (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning. https://topr.online.ucf.edu/assess-individual-learning-from-group-projects/.